The roofs of some of the buildings leak like dripping faucets. The water-pumps used by housewives for their household needs provide them with brownish rusty water. Amidst the narrow dark slots of a street, one can see playing children, who are the third generation of Palestinian refugees born in Lebanon.

The numerous refugee camps are little states within a state. Commune of nomads and outcasts brings up a generation of martyrs and fanatics. Living in misery and despair, they are ready to sacrifice their lives to a war without winners.

Pictures of suicide-bombers (for them – only martyrs) cover the walls of houses. »I was born against my will. I will die against my will. But I will live as I wish,» says an Arabic writing on the wall of a refugee house.

Shatilla of the western Beirut is known for a horrible massacre in 1982, when Israeli forces killed 800 Palestinians. The camp, whose narrow streets give shelter to some 20,000 people, is a memorial itself.

«We were in the other part of the camp and didn’t know about the massacre,» tells Nohad Hamad, who survived the invasion, “We only heard shooting, it lasted for three days. And then we saw a woman, running towards us, screaming and covered with blood. She cried, ‘They took my children, they killed my children! I held my children, while they were killing them. And now they are following me!»

The killing of Palestinians in Shatilla followed the assassination of Lebanese president Bachir Gemayel, backed by Israeli forces. Ariel Sharon, Israeli Defense Minister at the time, blamed the assassination on the Palestinians, and invaded Western Beirut.

The Palestinians, who don’t have a land of their own, are more homeless in Lebanon then in any other place. According to the laws, refugees are not allowed to have any property in Lebanon, or even to work legally. However, local authorities turn a blind eye on those who work for extremely low salary: refugees work without any guaranties or medical insurance here. Lebanese government doesn’t want to live with Palestinians, and can’t force them out, so it is trying to make their lives as miserable as possible.

«We’ve left all our belongings at our homes, hoping to come back soon when the fuss is over… Since that time we moved out of hundred places, and things are only getting worse,” says 69-year-old Om Rashid, who was born in Palestine, and now lives in a refugee camp in Western Beirut.

Funding for the only donor organization for refugees, the United Nations Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA) for 400,000 Palestinian refugees in Lebanon stands at only $52 million a year. Lebanese government only pays expenses of treatment for AIDS affected Palestinians, and UNRWA provides funding only for healing minor diseases, leaving the cancer patients on their own. Even those Palestinians who were lucky to get to school probably won’t get the higher education because of high expenses and low quality of secondary education for refugees.

«We established 5 secondary schools, 25 free medical centers… For the poorest of the poor we provide an every three month assistance, which is some amount of flour, rice, sugar and $10 in cash,» – said a spokeswoman for UNRWA in Lebanon at a press conference in a huge modern headquarters of the agency, located in a camp’s vicinity.

Hezbollah, a partisan movement established in the early 80-s to fight the Israeli occupation is cherishing the Palestinian dream of the return to their homeland. Although, like almost all other political parties in Lebanon, it strongly objects giving equal rights to the Palestinians with the Lebanese people. Freed from poverty, Palestinians would not remain a dumb weapon of the politicians.

«We’re not allowed to work 73 professions in Lebanon. Even those with degrees are allowed to work only in camps,» says Ms Hamad, who runs the educational centre in Shatilla, which trains 200 people a year to become hairdressers or typists. This centre, where also computer skills, Arabic, Maths and English are taught, is the only one in Shatilla.

«There is a world’s injustice towards the Palestinians… Refugees must go back to their land. Nothing else would solve the problem,” says Mohamad AI-Khansa, chief of Ghobeiry Municipality near Beirut, where Shatilla is located.

Palestinians believe, they will.

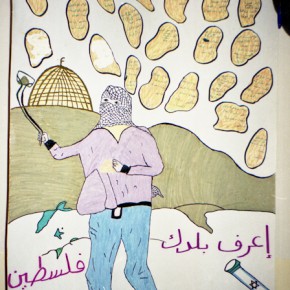

Small square room, were the nursery is located, is a place where 4-years old Shady, born in Shatilla, starts his education. There’s a big picture on the wall, painted by elder children: a Palestinian, carrying a sling in his hand, amidst rocket-bombs, marked with Zionist star. Names of children who are taught here to remember their motherland are inscribed on the stone blocks above. «Palestine is my home. And I will come back to my country one day,» says Shady.

Mines, limos, and Jesus Christ

«Why are we still young? ‘Cos time has left us here, it has left us behind…» sings Feiruz, whose voice is like a slow, warm 10-meter wave.

The downtown Beirut, underneath a big clock with luminous dial is a noisy and jolly scene. Tourists roam about the place 24 hours a day.

It grew colder, and waiters light the big mushroom-like gas heaters. Gleaming iron cap is reflecting warmth, and one can stay here, at a red-hot furnace for hours, smoking balmy nargille, a bubbling sedative, watching people, listening to Feiruz.

Smokers come to this place every evening to chat about latest news. Smokers arrive in different shapes and colors — there are Arabs wearing expensive Hugo Boss suits, Americans dressed in nylon jackets and sneakers, ladies in yashmaks, therefore unseen, and young girls with lustrous eyes. There are Christians and Muslims, sheiks in white turbans and youngsters with goatees and tufts.

Some of them are being helped out of their big Mercedes cars by their drivers or guards. They drive the rest of their way in wheelchairs.

Among them is 36-year-old Kemal, hurt by a fragmentation bomb 25 years ago. He would never walk again.

Though Kemal in his old crumpled Packard car is a lonely crippled gay, he lives in the other part of Beirut, beyond the green-line, which separates Muslim and Christian areas.

People beyond the line also smoke nargille and play backgammon, for even in the daylight foreigners who may be taken for Americans are unwelcome there.

Beirut hasn’t heard a machine-gun crackle or a mine explosion for years though all the streets approaching the governmental institutions are barred with antitank obstacles. Those streets hide little elegant police tanks – just in case.

The Holiday Inn, once a fashionable hotel turned to a monument of war. It used to be a base for snipers during all wars, and now its many-storeyed building, perforated with gunshots, stands like a muddy grey ghost amidst rebuilt markets and mosques.

Out of town and into the country, especially the southern part of it near the Israeli border, there are more and more signs of war.

Minefields left from the civil war and Israeli occupation still kill dozens of Lebanese.

Almost every Coca-Cola billboard is accompanied by the Hezbollah advertisement. Portraits of Hezbollah leaders, calling to fight with Israelis, can be seen on every house or a market wall in the South of Lebanon. The regular army widely cooperates with those partisan forces. Once Hezbollah exchanged Israeli minefield maps for a couple of hostages, thus strengthened its growing popularity among Lebanese.

Ali Fakhoury from a mine action coordination centre says the greater part of the territory is now fit for agriculture. Though some little rocky hillocks and desolate building may still be dangerous.

“You better walk on my traces. We could still find something, which is not a banana,” says Ali gravely, while we are examining the old mine fields of the south.

The southern Lebanon is where famous ancient Tyre resisted the siege of Alexander the Great for three years. Nearby is Qana, a little town of Galilee, a place where according to the Bible Jesus Christ turned water into wine.

Legends of ancient Phoenicia and sacred biblical places remain a great attraction for tourists from around the world, but a threat of a new war scares away travelers, who are the main source of income for natives of this land.

Aleksei Bobrovnikov

(from Beirut, April 2004)