exсerpt:

«The Edges of Georgia»

(Крайности Грузии)

by Aleksei Bobrovnikov

from Chapter 6: «Into the Khevsureti

through the village of Juta»

Lost in the mountains

«Khevsurs is a small but the most unique of all the wild

Christian nations of the whole Caucasus» —

Gustav Radde, «Khevsuria and Khevsurs».

Pagans or crusaders?

If Svaneti is the northernmost extreme point of Georgia, bordering on Kabardino-Balkaria of Russia, then Khevsureti in which the next chapter takes place can be called without exaggeration the most severe and unknown Georgian side.

According to one of the legends, there were thirty of them. The other claims there were three hundred. Different authors refer to different often contradictory data. However, all of the sources agree on one point: on horseback, in chain mails, with long straight swords, bearing small round shields a unit of Khevsurian warriors entered Tbilisi to offer the tsar their services in a new war. The war, which methods were still a dark mystery to anyone and more than anyone else to whose medieval fighters, who volunteered for that disastrous campaign.

Khevsurs knew nothing about tanks, poison gas and other modern mass-murder techniques, probed in the first big war. They did not come to the city to read the news as the main news was already known: the war began, and therefore who else if not the most savage mountaineers were to send their troops to Tiflis.

«Why did you come?» — they were asked.

Who were to ask them this question, and whether there was such a conversation at all is not so important: all the legends of the knights and prophets coming to the cities from the remote places begin with the question «why are you here?»

«We know that the Tsar has entered the war, so decided to help him» — answered the Khevsurs.

It was 1914. Or 1915?

The news was reaching the mountains late, and the order for general mobilization might have spread in some villages only with the spring mail. Maybe at that point, they started to get ready for that Crusade.

Artillery, the first tanks, airplanes. And a company of Khevsurs, dressed in knightly armor.

This story does not have a point — it ends on the words «we came to assist him…»

Such kind of people inhabited this region a hundred years ago.

Before I start my story about traveling to the country of Khevsurs, I want to turn to another story that will help to understand their character.

This legend is told about the Khevsurs by their compatriots. (When a Georgian wants to tell a foreigner a story about another Georgian, he almost always praises him, except when the protagonist of the story comes from the city of Kutaisi — Georgia’s recognized capital of scoundrels of all stripes.)

But let us return to the Khevsurs.

Once in a mountain village, men learned about the impending attack. Some powerful and very dangerous force was going to take over them.

These could be Kistins (present-day Chechens) or the militants of the Dagestanian Imam Shamil.

In a word, someone very strong and ruthless.

Khevsurs knew that they had no chance to win in that battle and if they lose, the enemy will abuse their women and sell children into slavery.

The latter, most likely, will be traded at the Istanbul slave market, where beautiful girls and handsome boys can expect a turn for a much easier, though shameful fate.

Then the Khevsurs called a military council. Neither prayers nor hopes — on that day they decided not to rely on a fortune: too much was put at stake.

The elders decided: before the enemy attacks they will kill all women and children so no evil hand will touch their beloved.

And they killed them all.

Maddened with fury, Khevsurs entered an unequal battle and… won.

This legend, like the previous one, does not have an ending.

We do not know what th e winners did next: have they stayed in their horrifying, deserted nest or abandoned it, scattered over the mountains. Or, perhaps, dressed in knightly armor, descended from the mountains to die in a new bloody civilized war.

e winners did next: have they stayed in their horrifying, deserted nest or abandoned it, scattered over the mountains. Or, perhaps, dressed in knightly armor, descended from the mountains to die in a new bloody civilized war.

These two legends better than any historical reports represent the people inhabiting the Georgian lands from the Bear Cross pass and further, to the gorge of the Argun River, the border with Ingushetia and Chechnya.

However, the plot that brought me to Khevsureti had nothing to do with military virtues or bloody vendettas of the past.

Once in Tbilisi, I was told about a curious rite which added to the image of Khevsurs the unexpected note of coquetry, and even a greater mystery to the reputation of the daughters of those cruel brutes.

«Tsatsali» or you can leave your hat on

«Have you heard anything about tsatsali?» — Gocha asked once. In a small Tbilisi tavern, we discussed the previous expedition to the mountains. Three people sat at the table: myself, Gocha — a tall, skinny fellow from Racha with cunning, humorous eyes, and Tato — a Georgian from Svaneti; a strong, muscular guy with an open face, who accompanied me during one of my trips to Mestia.

«Tsatsali? What is tsatsali?» — I’ve heard this word for the first time and therefore demanded an explanation.

«This is the Khevsurian tradition, a ritual of hospitality. If you find out what «tsatsali» is, then you will most probably have to stay here for good» — Gocha grinned. — «Just that the mountain pass is already closed, and you won’t be able to access Khevsureti this year. This is not Svaneti, with a new concrete road and the plane flying there twice a week. To get to Khevsureti you will have to wait at least six months.»

«So what is the tsatsali? Some kind of a Georgian rite?» — I asked, ignoring the first warning. — «Can you observe something like that in Svaneti?»

«Do you think our guest could ask your brothers-svanetians to organize him… hmm… the rite of tsatsloba?» — Gotcha turned to the svanetian with his ironic grin.

«No way!» — blurted out the latter.

For a few seconds looks of anger, bewilderment and, finally, joy, appeared on Tato’s face, extremely open and honest.

A broad smile plastered on his face after he finally realized that the guy from Racha was only kidding.

Now they both looked at me with the look of the parents, whom the annoying little rascal begs to lead to the roller coaster; the elders, tongue-in-cheek, reply: «do the homework first!»

«What is tsatsali, you devils?!» — I demanded an immediate answer, though none of them was seemingly willing to give up.

However, the game of cat and mouse could not last forever. The first to speak was Gocha who realized that keeping me in limbo for too long they risk losing my interest.

The essence of the rite of «tsatsloba», according to him, was that: the owner of the khevsurian house who invited the guest to the table, among the other orders given to his household called an unmarried girl into the room. It could be a daughter or a niece — anyone from his own kin, only with one condition: youth and virginity is a must!

The invitation of the head of the clan by no means was mandatory — her contact with the stranger is a chance but in no way an obligation. The girl has to decide for herself whether she wants to spend the night with the stranger.

«And so here it is… The rite of tsatsali!» — summed up the cunning Rachian.

«By spending the night you mean what I thought?» — I asked, stunned.

I have never heard of such frivolous traditions flourishing among the Georgian highlanders.

«No, it’s not about sex» — my companion replied. — «That night they will lie side by side but only on one condition: between them there’d be a dagger, which the girl could use in case the newcomer behaves in a manner, which does not apply to a trust that was put in him» — the skinny Georgian narrowed his eyes in a grin.

«I wonder, what this «does not apply to a trust that was put in him» could mean»? — I smiled back. «After all, this phrase can be interpreted either way. Perhaps in this situation… Well, isn’t all this tsatsali thing just about attracting fresh blood to the remote village?»

«Well, that’s precisely what you’ll have to find out» — answered my vis-à-vis, laughing in his scornful manner.

«You’re trying to say this ritual still exists?» — I asked doubtfully.

«No clue…» — answered Gocha.

«How is that?»

I was amazed that a person who lived in Georgia all his life may not know anything about such a basic thing.

«I do not know» — he repeated — «I’ve never been to Khevsureti in my life»

I glazed at Tato.

Svanetian shook his head.

«Neither have I»

In fact, I was not very surprised with Gocha’s reaction as this city slicker has never gone anywhere where his Mercedes car could not get him. But Tato, who traveled all over Svaneti and knew every pebble in the region that was just recently considered wild and untamed!

«How can you know nothing about Khevsureti?» — I asked imploringly.

«Because I’m Svanetian!» — Tato replied with dignity.

The matter seemed to end here.

What else can you learn from a Georgian who travels around his own country only out of necessity, paying visits to relatives on the occasion of funerals, weddings or baptism; settling the issues of inheritance or bringing home from the family cellar some sufficient amount of wine from the vineyard (if his parents are Kakhetians), or potatoes (if his family comes from Svaneti).

Regions with which the Georgian does not have a strong kinship tie simply do not exist in his realm.

«How do you know about the «tsatsali» then? — I asked them — «Just now you talked to me as if all your life through you’ve been wandering around mountainous villages — (at this point I turned to Gocha) — sharing beds with the daggers and Khevsurian virgins. And now it turns out that you have never set your foot on that land?»

Gocha only shrugged his shoulders.

At that moment, it became clear — while in Tbilisi you can talk to a hundred people, read a dozen books, but not get any closer to the reality happening just a hundred kilometers from the capital. Therefore it became clear: I can not do without a guide who will help me in the search for «tsatsali» and other ancient rites and rituals.

First encounter with the Guide

It seems we’ve brought the bad weather with us. The city of Tbilisi was wallowing and sniveling despite the brilliant weather forecast.

CNN weather and even the queen Tamar (our guide and intuition in Georgia) lost their way in their own forecasts.

Instead of the promised «plus thirty-two celsius. Plenty of sunshine on offer» with no mentioning of the «bubbling rain» we wrapped ourselves in raincoats dreaming about a gulp of Chacha, a Georgian grappa.

Chacha.

A favorite remedy for all diseases, a panacea for bad weather, flu, bad liver, cold feet, sore throat, broken heart, what not.

«Fifty grams of chacha before dinner is very useful for your health!» — said our host Mamia, when we crossed the threshold of his hotel.

«He would say the same thing in the morning, before breakfast» — says my colleague, — «I know this guy.»

Mamia brings a bottle two-thirds full of strong grape vodka.

There are several of his friends at the table. We see them for the first time, but they smile like old friends and call us to join their meal.

«50 grams of chacha is very good for colds» — claims one of them, noting that one of us has a running nose.

«A glass of Chacha immediately cures a cold. Instantly» — confirms the other.

Judging by his appearance it’s not even that he has never got a cold in his life, moreover, he finds it impossible to understand how one can get a cold at such a beautiful sunny day.

He does not know that the skies have opened up and is truly surprised to see our wet hair.

For this guy, the time has stopped around noon the other day when he dropped by to pass the glass or two.

So, we were there.

Tonight, for the first time, we have to meet our guide, Koba.

In our first conversation over the telephone, he made a gravely serious impression that involuntarily reminded me of his terrible predecessor.

«My name is Koba» — he has introduced himself.

«Koba derives from…?»

»Koba. Simply Koba» — the man replied.

Hearing this, I imagined a limping dictator in a military jacket and a pipe. The scariest Georgian of all — Joseph Stalin, born Jacob (Koba) Jugashvili.

Meanwhile, my new acquaintance spoke slowly and pulled out of me everything I knew about Khevsurs and their capital — the fortress of Shatili. I felt like I’m trapped in a spiders net and the tender chitinous cover of my knowledge on the subject is now exposed as a dead fly shaking in the web. It was almost a physical sensation: a cold and uncomfortable feeling of being unarmed. Each question seemed a test, a cunning trick.

His quiet, full, as it seemed to me, mockingly tranquil voice, made me forget even those scarce facts that I knew about the customs of the khevsurian highlanders.

Koba was looking right through me. Indeed, I did not know anything about Khevsurs and their mysterious rite of «tsatsali».

«Good» — Koba said at last — «You will find it out all this on the spot. Rely on me.»

Now it has become absolutely clear that whether I want it or not, we were in Koba’s hands.

The meeting with him was scheduled for this very evening, nine o’clock sharp.

Koba shows his hand

It was already half past ten, and Koba still has not shown up. His mobile telephone responds with a female voice with a strong Georgian accent: «the person you are trying to… cannot be reached…»

When Koba finally made an appearance, it was around midnight.

He turned up not quite the way we expected.

Gocha’s phone rang. Queen Tamar reported that Koba appeared at her door-step.

The reaction of her husband resembled a desperate light cavalry counterattack on the seized fortress. We left the meal and the unfinished glasses and rushed headlong to the car.

Never before have I seen Gocha in such a mood: exceeding all the permissible speed limits, we rushed in the direction of her majesty’s residence.

A person whose appearance could cause such a drastic change in the mood of the most balanced and calm of the Georgians ever known to me should be a person of outstanding character.

I prepared to watch the fight of dragons.

Gocha galloped up the stairs and rang the doorbell.

A doorbell, just like a phone call, always conveys the emotion of the person who presses the button. That is why the calls of soulless electronic devices can be frustrated or quiet, gentle or wooing; fierce, persistent and hysterical, and if this quality is connected to the voltage, then it is not necessarily the voltage in the electric wire.

This time the sound of a door-bell was striking like a dagger; it seemed to signal that the Georgian husband who guards his fortress always arrives all guns ablaze.

A moment later (as if Tamara was just waiting for him to return at the doorstep), the key turned in the lock.

Seeing his queen safe and intact Gocha slowed his pace. Entering his legal domain he was again filled with tranquility and dignity as befits a royalty.

«There he is» — Tamara said meaningfully, pointing inside the room.

Following the owner into the living room I expected to see a man armed, if not with a rifle and dagger, then at least with the charisma of the darkest leader of the humankind.

Crossing the threshold of the living room I looked at the sofa where Gocha’s gaze was directed. There, peacefully curled up, slept a man in black golf and a kind of sneakers, reminiscent of a football dream of a schoolboy from the late 80’s.

«Koba!» — called Gocha.

There was no answer.

«Koba!» — he repeated.

The man shuddered, stretched his limbs and then as if realizing that he was not at home, sat up sharply and stared at us with his dimmed, bleary eyes.

Then he murmured something in Georgian. It seemed almost incomprehensible, though Gocha laughed in response.

Then he uttered a few phrases.

Koba seemed to come back to this world.

Their conversation contained the words «tsatsali» and «Khevsureti»; words, that have already puzzled me.

«We are kicking off tomorrow» — Koba’s voice suddenly resembled the one of Joseph Stalin, giving the orders to annex Poland.

And, as if nothing happened, he lit a cigarette and, began to draw a plan of our route.

In just a few minutes nothing would suggest that dreary hapless creature we found on Gotcha’s sofa less than a half an hour ago.

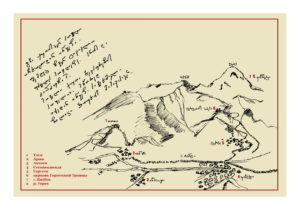

We agreed to leave Tbilisi early in the morning, follow the Georgian Military Road deep into the Khevi region, populated by a people called Mokhevis. (By the way, both names — Khevi and Khevsureti — come from the Georgian word, meaning «gorge»).

In the first day of the trip, it was decided to pass the settlement of Stepantsminda and the picturesque church of the Gergetis Trinity (Gergetis Sameba), cross the Truso gorge and get to the village of Juta — the last point of the route in front of the Khevsur country.

In the first day of the trip, it was decided to pass the settlement of Stepantsminda and the picturesque church of the Gergetis Trinity (Gergetis Sameba), cross the Truso gorge and get to the village of Juta — the last point of the route in front of the Khevsur country.

But before going to Juta, we stayed overnight in an old Ossetian village near the Cross Pass.

Eagles from Toti Barrow

«When the last rays of the sun were dying on the snowy peaks, I was still under the heel of Tot-Gog mountain. Covered with a dark shadow it appeared as a black and formidable giant. It was completely dark when I arrived in the village. The Ossetians greeted me with a burning rushlight and hospitably offered shelter in the best hut… The next day, with the rising of the sun, I glanced over the village of Tot. It consists of ten stone houses, mostly built in two tiers and standing near each other. On the western side of the village on top of a tall granite mound, a small square Ossetian altar is erected from stone slabs of rough workmanship. It’s called «kivzet» and it is surrounded by sacrifices consisting of tur and deer horns».

An extract from «Tiflis Vedomosti» newspaper, 1830.

Toti. This is how this place is called nowadays. None of us knew anything about it when we decided to spend a night in an abandoned village.

It is located high on a mountain near a large stone mound, which at first seemed an ordinary little hill or an old shattered rock covered with grass and small prickly shrub.

«This is an Ossetian village. Once there lived one old man. But he is no longer there… No one lives there anymore» — said the man in one of these small roadside stores, those universal Georgian vendors under the signs: «Tea. Coffee. Vulcanization» that sell almost anything (at least tea and old tires can be found there for sure).

The village up the hill was completely deserted.

The houses still had large earthenware jugs for wine. The jugs, of course, were empty.

Judging by the marks and writings on the walls we were at least 50 years late for the farewell party if there was any.

Local residents were not leaving their homes in a haste. They left the place gradually: family after family, house after house, clan after clan…

Several years ago someone was still seen here: the owner came to visit his old dwelling.

Once a keen, eagle-eyed man spotted him from below and so he told his neighbors: «Look, there is old Musa. He is still up there, on the hill»

For several days in a row that roadside village down the hill talked about old Musa from Toti.

And then he disappeared again.

Since then no one has ever been seen on the mountain of Tot-Gog.

That night we pitched a tent on the long wooden balcony of the old stone house. There was a long night of toasting and prayers, as Georgian toasts are like short prayers for each other, for victories, for those, who are gone.

We prayed until midnight.

As soon as I rubbed the sleep and the midnight toasting out of my eyes and peeked out of the tent, I saw a completely different landscape.

It was all gleaming white: the mountains, the valley, the slope along which we climbed.

And right through the gorge, less than a mile away from us, in a V-formation like a squad of jet-fighters, flew a family of eagles.

I’ve noticed them just in time. In a less than a minute they disappeared behind one of the mountains that blocked the view of the road leading to the village of Stepantsminda and further towards Russian Vladikavkaz: the Georgian Military road.

Later that morning I climbed a little hill, the mound that, at the time of an 1830 publication, had a sacrificial altar on top.

That hill was still towering over the abandoned village.

Up there on the mound, clutching at a stone with my hand to help the ascend, I felt an unpleasant, warm mucus in my palm.

Yes, that was it…

I am not an ornithologist, but what else it could be on the very top of the hill on a clean stone without a trace of a living being?

I am not an ornithologist, but what else it could be on the very top of the hill on a clean stone without a trace of a living being?

On my way back to the camp I showed my dirty hand to my companions.

«Congratulations,» said one of them. «You got it…»

«Well, this is eagles poop!» — I stated proudly.

«Do not flatter yourself» — was the answer.

I did not argue with my companions.

What do they know about eagles ways!

Khevsurs, the way we will never see them

I do not intend to bore the reader with lengthy passages about Khevsureti the way it is depicted in the monographs of the Russian Imperial Geographical Society of the XIX century.

Nonetheless, I want to bring to light some of the most interesting observations on a portrait of Khevsurs as they appeared in that cruel and romantic golden age of adventure.

«The type of Khevsur rather resembles an ancient Zaporozhian or Scythian or Sarmatian: same shoes, same trousers, a short dress, a broadsword, thick hair cut in a circle, the same mustache and a short beard; brave, manly faces and mops of hair of those ancient Cossacks…» — wrote countess Uvarova, who traveled to the Caucasus for many years and left a few volumes of rather interesting travel notes.

«Khevsur is rude, arrogant, picky, proud and carefree. He only respects the bravery and considers himself above all nations. (…) Khevsurian girls under the age of 16 are very nice and slim, but the hard work, untidiness and rough food make them at 25 look like old women. Those are extremely ugly and, according to some eyewitnesses resemble witches from Kiev» — writes journalist Arnold Zisserman, who lived in the Caucasus for a quarter of a century and helped Leo Tolstoy himself to collect material for his works describing the local habitat.

Travelers of the XIX century depicted Khevsurs as pagans whose religion is a mixture of Christianity, Talmudism and ancient rites resembling the ones of the Druids.

«According to the concept of Khevsurs, there is a God of the East and a God of the West; God of souls, Christ the God, great God, and a little God. The people respect the God of war and the son of God most of all the others, but no one can explain to you the true tenets of their religion» — that quote we find in the anthology of articles on Khevsureti collected by certain N. Dubrovin and issued under the framework of Russian Emperor Geographic society.

The famous British anthropologist James Frazer has described in his study of magic and religion the ritual of «plowing the rain»: the witchcraft of Khevsuretian women calling for rainy weather.

Frazer recorded similar rituals in Romanian Transylvania and some parts of India.

The altars and temples, located in the wilderness of the forests add to the paganism of Khevsurs, as well as the cult of Hevisbers (literally — «the elders of the gorge»), who acted as mediators, shamans, and healers at the same time. Honoring the sacred groves, believing in angels living in certain trees, — all these rites resemble the faith of the Druids.

In «The History of War and Russian Dominion in the Caucasus» there is a mentioning of an oak tree growing in Khevsureti. That particular tree was nicknamed Bagration in honor of the famous Georgian royal dynasty.

The locals considered this oak to be sacred, and if someone from the male descendants of a glorious family came to Khevsurs and, hugging an oak tree, proclaimed: «My ancestor, do protect your descendant!» the Khevsurs were obliged to support the member of Bagrationi clan with all their might.

The books of ethnographers and travelers contain many interesting facts and myths from the life of this people, but none of the books shed any light on the rite of «Tsatsloba».

Therefore «tsatsloba» (or, in other transcription, «tsatsali») rite remained a mystery; a phenomenon that I only heard about from conversations with several educated Tbilisians.

Going to Khevsureti a year after the conversation I’ve cited at the beginning of this chapter I was no more aware of the mysterious rite of «tsatsali» than on the day when I first heard this Georgian word.

(…)

Mercenaries of the Transylvanian Prince

One curious detail for many years haunted journalists who wrote about the Caucasus. It is the weaponry of Khevsurs, resembling the ammunition of the knights in the times of the Crusades.

The long straight swords and shields of Khevsurs are almost a match to those used during horse fights in medieval tournaments and are strikingly different from the armor used by the neighboring Caucasian people.

This fact gave rise to various theories, the most romantic of which was the one about the knights of the Teutonic order, who allegedly wandered into the mountains of Khevsureti. So the story goes that some of them remained there to introduce the contemporary European fashion to the highlanders tribal culture.

«It is very difficult to recognize the descendants of the Crusaders in those people, for nothing defends the credibility of that theory: neither the type of Khevsurs nor their customs» — writes Uvarova — «The Khevsurs, they say, are fencing, but look at this fencing, these twisted, jumping figures, and you will probably agree that fencing is not brought into these mountains by medieval knighthood, but rather borrowed from some primitive wild people.»

Discussions on the topic of whether Khevsurs can indeed be the descendants of the Teutonic Knights have been going on for more than a century, but no one ever mentioned the other theory that was indeed far closer to the reality.

The Khevsurian role in the Crusades.

At the end of the XV century, when the Vatican tried to unite the states of Europe in the struggle against the Ottoman Empire, one of the most talented commanders of its time, whom the Holy See was counting on in its military operations was the Transylvanian prince who later became the Polish king. His name was Stephen Báthory.

The campaign which he supposed to lead, was canceled by the Papal throne, though Báthory became famous for other battles were the hussar battalions, including Cherkess and Georgian troops took part.

These facts are widely known, but few people dug deeper, learning who those Georgians were… And I would have never ever thought about Khevsurs if it were not for the article I have accidentally discovered in the «Kavkaz» newspaper (No. 24, 1851)

«Getting ready for his business, khevsur is all locked in iron. He puts on his head «chichkans» (also known as «szyszak» in Poland or a German «zischägge» — the type of a helmet covering the neck with a ring armor), a coat of mail, gauntlets, straight broadsword and a «dashna» — a short sword used instead of a dagger. Notably, all shields and swords have the inscriptions on them: «Genua, Souvenir, Vivat, Stefan Batory, Vivat Husar, etc.»

So, viva Stephen Báthory and his Khevsurian Hussars!

As If the then anti-Ottoman crusade under the Polish rule indeed had taken place the Highlanders from Khevsureti under the flag of the former Transylvanian Prince Stephan Báthory could become new crusaders waging war against the Eastern infidels to increase the glory of the Christian god and the papal treasury!

Mountain tea

«In the westernmost corner of the Chaukhi range are the springs of the Black Aragwa river. In the area of these springs, there are only rarely visited narrow paths of mountain hunters, often interrupted by the scree slopes; these paths lead to the east, past Chaukhi, to the land of Khevsurs…»

— From the «Notes of the Caucasian Department of the Imperial Russian Geographical Society».

Tiflis, 1881

Of all the mountain plants climbers hate tea the most. No, not the dried, crushed leaves that need to be poured with boiling water, the refreshing delight of every traveler, but that wild slippery verdure under your feet the locals call the same name.

You never know what is beneath it: is there a crumbing scree or a solid rock and whether this rock holds well, or is it just a moss-covered small stone that rolls down one’s one steps on it.

Now they were just about to step on those tea fields on the slope.

This party did not look a group of climbers. Only one of them, who was ahead of the others, was wearing proper mountain boots. The one who followed was wearing ordinary sneakers, and the third, who walked in arrière-garde, was in open sandals.

All three carried backpacks, but only two had alpenstocks, those special walking sticks for hiking in the mountains. Instead of two these travelers had only one stick for each.

The last in their group went without any sticks at all, clutching at the stones with the bare hands.

«Do you know what would be the most pleasant thing for me to see now?» — the second in the group asked the one who walked behind. «The cow shit! As if a cow could climb here, then a human could easily do the same»

But there was no cow dung up there. There was nothing there at all, except small, crumbling pebbles under their feet.

Ahead, on the steep slope were thickets of those little slithery crops — the so-called «mountain tea».

If only the old man Khuta could see them now!

«I did it with their mother… these climbers. Look how they walk!» — that’s what he would say. That was his usual parlance when he observed a striking disproportion — the climber with a huge backpack, but without any ropes and alpenstocks.

Look at him, as he crawls, almost on all fours, like prehistoric people, but with a huge, modern backpack, with a built-in iron frame and dozens of mounts for ice axes, ropes, you name it… A backpack that looks like a spacesuit piece, but is completely useless now, when they did not have the most important thing — the ropes.

«I did it with their mother…» — Khuta would grumble when he saw such an expensive, fashionable backpack on a dumb novice’s shoulders.

Such equipment was not known in those times when he himself, Khuta Khergiani, was climbing Everest.

«The first Georgian mountaineer to join Everest expedition» — that is what is needed to be said as a part of the chalk-talk before any story on Georgian climbers.

«Are you tired, mister Khuta, batono Khuta?”— the youngsters would ask him at the end of a hard day in the mountains, or at three o’clock in the morning, at the end of a particularly exhausting supra, the feast, when everyone was already falling from his feet.

In the meantime he, the big Khuta, was still holding the thread of a conversation firmly, sipping wine from his makhshvi glass — the glass of the Svanetian chief of the clan.

«Have you slept well, batono Khuta? Don’t you need a little rest?» — someone among the guests would ask pleadingly, secretly intending to sneak out of the table, but not daring to do so without the permission of the makhshvi, the chief.

And so Khuta as if nothing had happened, sits there with a calm smile of a very tired, but also a very strong person.

«Didn’t I got enough sleep?.. Ha, after Everest, I still can’t get enough sleep» — Khuta smiles and so everyone does, echoing him, nodding their heads.

And Khuta begins to recall his ascent in the 1982nd, and no one is in a hurry any longer, and the wife of a mountain climber serves freshly baked kubdari — Svanetian meat pies, seasoned with spices and mountain herbs…

Meanwhile, there, in the mountains, the slope became steeper, and if those who were leading the group could still walk on their two, helping themselves with the alpenstocks, the last in the group had no choice but to slide downhill, like a surfer, on crumbling ground.

«Where are these clowns heading?.. I did it with there…» — now the old mountaineer would utter with sadness because they would only see what they could see, and they saw nothing while at the bottom, a hundred meters away, a different story began to unfold: sheer cliffs at the end of the slope.

«Cows shit. Damned cows dung… if only I could find it here» — one of them muttered to himself.

There was not a hint of a trail.

Did they miss it? Or did they started descending too soon?

«If we get to that glacier» — the guide said, — «then in five kilometers we could reach the Abudelauri lakes… That’s where we’ll camp».

He did not have time to finish the sentence, as his companion walking ahead suddenly stopped, peeped down, and then cautiously backed away on his four.

Two others froze, watching him.

«This stream!..» — he cried out.

The man’s voice sounded as if he was out of breath, though he was not running anywhere.

Before he finished the phrase he stopped to take a deep breath.

«In short, there is no path! There is a cliff right down there!»

The guide crawled up to the edge of the ledge and looked down.

The glacier, their landmark, was visible from that point. But right in front of them, there was a sheer rocky cliff. The waters of the stream were falling from a twenty-meter height. That stream-bed just a few minutes ago seemed to them a reliable trail.

«It’s good that we didn’t go as I suggested at the start!» — one of them said.

The guide said nothing.

His face expressed no emotion — neither disappointment, nor surprise, nor anger.

If only they were more attentive, they would have noticed before. But they could only look under their feet and curse, watching the small pebbles slipping out from under their feet.

The mounds, which seem to be a solid ground, crumbled at the slightest touch, like a rotten old cloth that you take in your hands and suddenly throw it away with disgust as the thing you throw away is not even a fabric, but a ragged, loose, moth-eaten, sandy rag.

If only the old alpinist could see them… If the fog, that already took over the mountain above, comes down their slope they would not be able to help themselves. In fact, no one could help them then. If old Khuta was there they would have camped before the very start of that descent and wait for the weather to change. Uphill in a thickening fog, they would warm up water on the camp stove, chewing churchkhela (this Georgian snickers bar — dried bars of walnuts in a grape juice, thickened with flour) and ranting about this and that.

An experienced climber would never have tried that slope in a fog, Or, if he was already within sight of it, he would immediately turn back in front of the slippery surface. He would force them to climb back to the first ledge, set up camp there and wait.

It was necessary to do it urgently until it started to rain.

No, Khuta would not allow this descent. Not even because it was too dangerous, but just because the risk was pointless.

No, Khuta would not allow this descent. Not even because it was too dangerous, but just because the risk was pointless.

Though these fools were not climbers… and they kept going.

Passing a small stone ledge they went out onto a slope covered with the herb, locals called «tea». The ground under their feet disappeared beneath the dark green leaves becoming wet under the rain.

It started raining harder when they reached the middle of this wild tea plantation, a slope covered with a small, ankle-deep shrubs having large, flat, shiny leaves resembling dark green satin.

The tea plantation on the dev’s, those mythical ancient Georgian giants, that’s what it was. After all, there should have been someone planting it there for the tea cannot grow on the Earth just like that, aimlessly, without a purpose.

The tea leaves glistened as the drops of rain rolled down them into the loose soil.

«Where are they going! Where are they going, I did it with the mother!..»— one of them muttered to himself thinking of his group in the third person, remembering Khuta, the old climber, who took hundreds of young suckers into those mountains, pretending to be climbers and repeating all imaginable mistakes of the reckless novices.

It was already too late to change the route: now, in the rain, there was no chance to get back to the starting point so there was no other choice but to make their way forward.

For those who had alpenstocks in their hands, this tea plantation was still a cunning enemy. Unable to see anything under its leaves they use their alpenstocks as the blind man uses his stick trying to guess what this dark glassy greenery was hiding beneath its surface.

For the one who walked barehanded this tea became a salvation — clutching at his strong, woody stalks with his hands, he made his way forward like a spider.

Two of them cautiously watched the one who was ahead of the group as if this descent would also end with a cliff they would be cut off completely as the slope along which they had just descended was no longer available to a climb.

This «plantation of the dev’s» was over, but the descend didn’t get any easier.

They now stepped on a moss-covered hill along which dozens of small streams flowed. The rainwater, filtered through loose soil, filled the beds of the small springs, which became wider and wider each minute as the rain was getting stronger.

Now the water was dripping from the very mossy soil.

It really was velvet — dark, wet velvet through which, mixed with rain, the icy glacial water flowed.

Sliding, barely keeping their balance, they reached the narrow ridge — the only reliable place on this entire slope.

Right there before their eyes was a glacier. Old, gray, dirty as if stained with watery Turkish coffee, but still strong despite the August sun.

When a man in sandals, the last one in a chain, set his foot on the ice, the two others were already sitting on the backpacks, smoking and looking at a waterfall eating through a thick white shell of the glacier.

When the last of them has reached the group he also asked for a cigarette and smoked looking at the rocks and the steep cliff that they had just managed to pass by.

They sat there for half an hour, ate chocolate, spat on the icy surface and made fun of themselves and their adventure, still not quite understanding where they had just come from.

The one who was in sandals got his mountain boots from a backpack.

«It’s getting cold,» he said, «time to wear a warmer pair of slippers.»

And they went on, smoking, spitting and laughing. On the hill, a few hundred meters ahead, they saw the first cow pie among the huge boulders.

So they crossed into the land of Khevsureti.

Or they just thought they have crossed…

(…)